2025 Global Hunger Index

This year marks the 20th edition of the Global Hunger Index (GHI), a critical tool for tracking and driving global efforts to end hunger. Yet instead of celebrating sustained progress, we are sounding an alarm: progress in reducing hunger has stalled, and the world is drifting further away from the goal of Zero Hunger by 2030. This isn’t due to a lack of warning signs. It’s the result of a collective failure to act on them.

The halt in progress reflects the compounding impact of overlapping and accelerating global crises, from intensifying armed conflicts and climate shocks to economic fragility and political disengagement. Among these, conflict remains the most destructive force driving hunger. Over the past year alone, violent conflict fuelled 20 acute food crises, affecting nearly 140 million people. The devastation wrought by the wars in Gaza and Sudan offers stark evidence of how conflict obliterates both livelihoods and lifelines, leaving long-lasting scars on food systems and human lives.

But history shows that course correction is possible. Between 2000 and 2016, global hunger declined significantly, even amid global financial downturns and natural disasters. This progress was made possible by coordinated action, sustained investment, and political will – tools still available to us today, if we choose to use them.

The 2025 GHI paints a sobering picture. Despite early gains, global hunger levels have stagnated since 2016. The global GHI score now stands at 18.3, only slightly improved from 19.0 in 2016, remaining firmly in the moderate category.

At the current sluggish pace, Zero Hunger by 2030 is no longer a realistic goal. In fact, projections suggest the world may not achieve low hunger levels globally until 2137, more than a century from now. At least 56 countries are not on track to reach even low hunger by 2030.

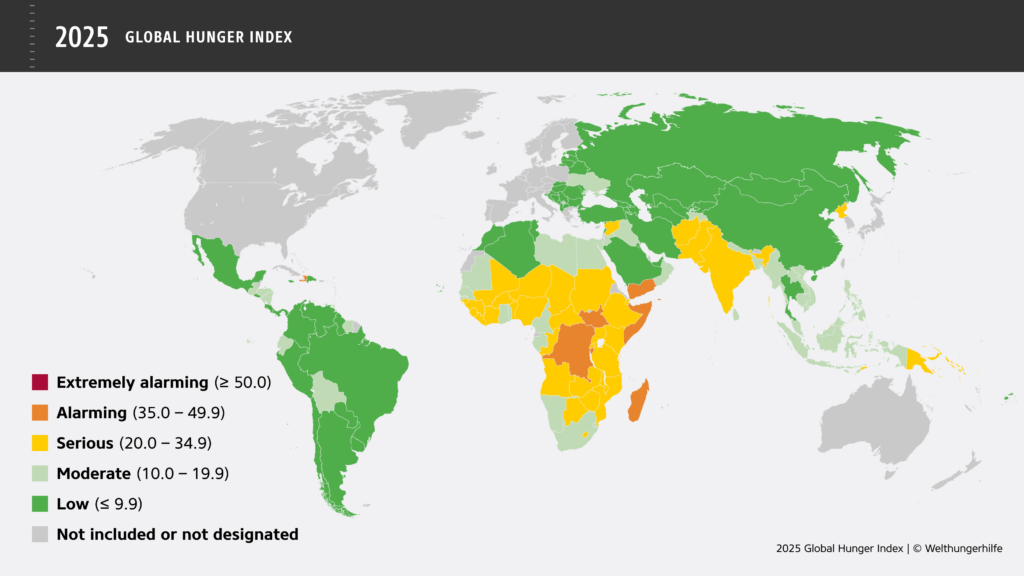

Worryingly, hunger has worsened in 27 countries since 2016. In 7 countries (Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Madagascar, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen) hunger is at alarming levels. An additional 35 countries face serious hunger.

The true extent of the crisis may be even greater. In contexts like Burundi, DPR Korea, the occupied Palestinian territories, Sudan, and Yemen, data gaps obscure the reality. However, available indicators point to worsening conditions, creating a dangerous cycle: unseen needs receive no aid, and neglected hunger grows.

The burden of conflict is again underscored. Between 2023 and 2024, famine-level food insecurity (IPC 5) more than doubled to 2 million people, largely due to the wars in Gaza and Sudan. Meanwhile, global humanitarian aid budgets have shrunk, even as military spending climbs, reflecting an alarming inversion of priorities.

Regional disparities remain stark. Hunger is still serious in Africa South of the Sahara and South Asia, while modest improvements in undernourishment have occurred in parts of South and Southeast Asia and Latin America.

Yet there are beacons of progress. Countries like Mozambique, Rwanda, Somalia, Togo, and Uganda have made notable strides, with more than 5-point reductions in hunger since 2016. Examples from Angola, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India, Nepal, and Sierra Leone demonstrate that targeted policies and sustained investments can lead to real, measurable change. However, these gains are fragile, underscoring the need for resilient food systems, early-warning mechanisms, and long-term political commitment.

You can find the full 2025 Global Hunger Index Report here.

About the GHI

The Global Hunger Index is a peer-reviewed annual report, jointly published by Alliance2015 members Concern Worldwide, Welthungerhilfe, and the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV), designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger at the global, regional, and country levels. The aim of the GHI is to trigger action to reduce hunger around the world.

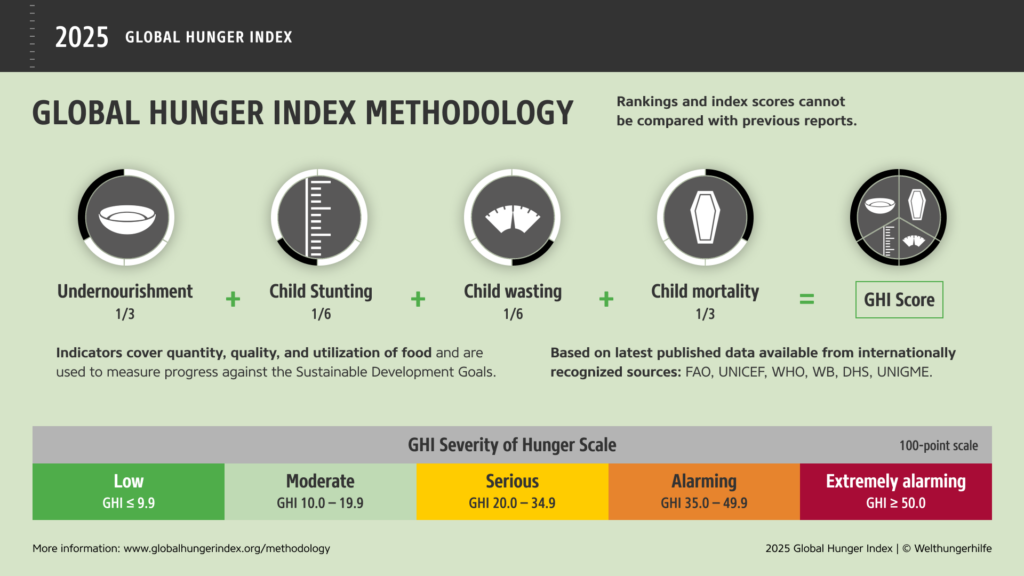

The GHI ranks countries based on four key indicators:

- Undernourishment: the share of the population with insufficient caloric intake;

- Child stunting: the share of children aged under five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic under-nutrition;

- Child wasting: the share of children aged under five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute malnutrition;

- Child mortality: the share of children who die before their fifth birthday, partly reflecting the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments.

Countries are scored on a 100-point severity of hunger scale where zero is the best possible score (no hunger) and 100 is the worst:

- Extremely alarming: equal to or greater than 50;

- Alarming: 35 to 49.9;

- Serious: 20 to 34.9;

- Moderate: 10 to 19.9;

- Low: equal to or lower than 9.9.

Cover: Mikkel Ostergaard/Panos Pictures, Ethiopia, 2012